19/04/2024

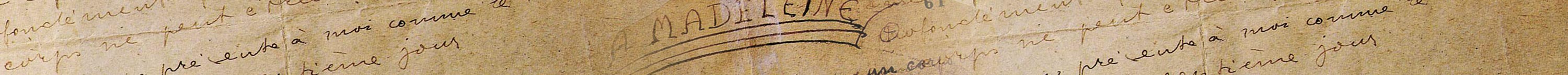

Extrait d’un carnet du mathématicien Oswald Veblen (Library of Congress).

Programme

Caractériser et mesurer la courbure: Explorations diagrammatiques autour des brouillons de Leibniz et ses amis

Au début des années 1680, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz entreprend des recherches pour caractériser la courbure en tant que grandeur. Ses recherches aboutissent à une première publication en 1686 intitulée Meditatio nova de natura anguli contactus et osculi… Il y introduit les concepts de cercle et d’angle d’osculation qui lui permettent de donner un sens mathématique à la notion de courbure, et par ce biais à celui d’ « angle entre deux courbes ». L’article montre que Leibniz n’est cependant pas pleinement parvenu à fournir un moyen de mesurer la courbure, ni à caractériser précisément le cas extrême que constitue dans ce contexte le point de flexion. Ces insuffisances se retrouvent en revanche dans certaines tentatives et tâtonnements qui apparaissent dans plusieurs passages fortement diagrammatiques de manuscrits à l’origine de cette publication.

Dans cette intervention, je souhaite retracer un des chemins de la genèse conceptuelle de la courbure à travers les brouillons de Leibniz, mais aussi en analysant certaines questions posées dans les échanges épistolaires entre deux autres mathématiciens contemporains de Leibniz – Guillaume de L’Hospital et Jean Bernoulli – questions qui débutent en réaction à cette publication.

Discussion par David Waszek (ITEM, ÉNS)

Where Mathematical Symbols Come From

The role of formal systems and of symbolic and diagrammatic notations in general has received considerable attention by philosophers of mathematics in the past. However, few have paid attention to particular symbols and their shapes. If they are considered at all, it mostly about when a symbol was used for the first time and by whom. The reason for why philosophers have rarely considered reflecting upon the role particular symbols and their shapes is because they are generally considered to be arbitrary and purely conventional, i.e, arithmetic would be no different if we would replace the numeral « 8 » by a different symbol. Nevertheless, I will argue in this talk that the shape of many mathematical symbols is in fact well motivated. In a nutshell: In mathematical practice, symbols are not arbitrary.

I will discuss several possible motivations for the introduction of new mathematical symbols. These include (1) practical reasons, such as ease of writing or availability for printing. Considerations about (2) human perception, i.e., for reading, and about (3) human cognition can also guide the choice of symbols. Mnemonics (such as the Greek letters delta and pi for the diameter and periphery of a circle) and the use of inverted letters to indicate inverse relations reduce the cognitive effort to memorize the meanings of the symbols in question. More important for philosophy of mathematics, however, are (4) semantic reasons for the choice of symbols. Here, a symbol is chosen either because it has already a meaning that is related to the new one, or because the symbol itself evokes the meaning that it is intended to carry.

A better understanding of the motivations behind the shape of symbols can thus provide us access to the conceptions that mathematicians have of the subject matter they investigate and contribute to a richer picture of mathematical practice.

Expérimentation manuelle et par ordinateur dans la recherche en combinatoire

En tant que chercheuse en combinatoire algébrique, l’approche exploratoire est essentielle à mon travail. Mon processus de recherche est un va et vient constant entre des expérimentations manuelles (calculs, énumération exhaustives de structures, cas particuliers, etc) et sur ordinateur. Dans cet exposé, je me baserai sur un problème en cours pour dérouler le processus de recherche qui m’amène à obtenir de nouveaux résultats.

Discussion par Baptiste Mélès (Archives Henri-Poincaré – Philosophie et Recherches sur les Sciences et les Technologies, CNRS)

Lieu

Site Pouchet, 59/61 rue Pouchet 75017, Salle 159 et en visioconférence (emmylou.haffner [at] ens.psl.eu pour le lien).